Security Pros Love Python? and So Do Malware Authors!

This is a guest post submitted by Ismael Valenzuela.

Learning how adversaries compromise our systems and, more importantly, what are the techniques they use after the initial compromise is one of the activities that we, Incident Responders and Forensic/Malware investigators, dedicate most of our time to. As Lenny Zeltser students know, this typically involves reverse engineering the samples we find on the field by means of static and dynamic analysis, as for the majority of incidents we encounter, we end up examining a compiled Windows executable for which we have no source code.

However it seems that it’s not us only, fellow readers of the SANS ISC, that are huge fans of Mark Bagget’s posts and his Python classes. It turns out that malware authors are too! Why would attackers use Python to write malware? One of the reasons may be that it is easier to reuse blocks of code across different malware samples, and even platforms. As I always say, “attackers are lazy too”, and they will certainly reuse as much code as they can. However one of the most powerful reasons is probably the fact that AV detection rates on binaries built with Python packers (like Pyinstaller) tend to be quite low.

This method represents a huge opportunity for us though, since ‘reversing’ these binaries is a straightforward exercise. Let’s take as an example a binary that I first captured on the field a few months ago, and that it can still be seen today in different variants.

This binary is named servant.exe:

MD5 (servant.exe) = 9d39cfab575a162695386d7e518e3b5e

And was found under the user’s %APPDATA% directory on a system that exhibited some suspicious behavior, including connections to servers hosted in Turkey that already had a dubious reputation (I assume that you’re looking at your outbound traffic too, right?)

Let’s have a look at the binary now. A simple strings on servant.exe reveals the presence of many python related libraries:

bpython27.dll b_testcapi.pyd bwin32pipe.pyd bselect.pyd bunicodedata.pyd bwin32wnet.pyd b_tkinter.pyd b_win32sysloader.pyd b_hashlib.pyd bbz2.pyd b_ssl.pyd b_ctypes.pyd bpyexpat.pyd bwin32crypt.pyd bwin32trace.pyd bwin32ui.pyd bwin32api.pyd b_sqlite3.pyd b_socket.pyd bpythoncom27.dll bpywintypes27.dll xinclude\pyconfig.h python27.dll

Also, one of the indicators that caught my attention when looking at this system was that the file python27.dll (along with other .pyd and .dlls like sqlite3.dll) was ‘unpacked’ on the same directory as the executable.

This is somewhat expected. If servant.exe is built with Python, it would require all the external binary modules to be in the same directory in order to run successfully. Alternatively, these files can be built also into the same self-contained binary, running without any external dependencies. One of the most popular tools used for this purpose is Pyinstaller, a tool that can ‘freeze’ Python code into an executable, and that will prove very useful in our next step.

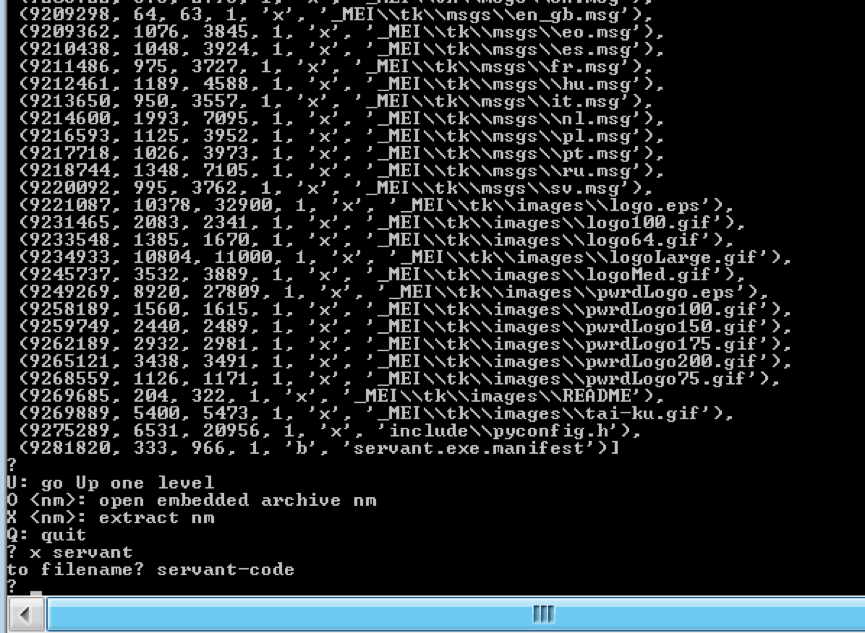

How difficult is to ‘reverse’ (rather unpacking really) this sample? As difficult as using one of the command line tools included with the Pyinstaller package, pyi-archive_viewer. The following command allows you to interactively inspect the contents of an archive file built with Pyinstaller:

c:\Python27\Scripts>pyi-archive_viewer.exe servant.exe

After listing all the contents of the archive, you can extract any file using the command ‘x filename’.

The resultant file, servant-code, will contain the source code for this malware sample. Alternatively, there are several scripts available that will automatically extract all the files for us. One of them is ArchiveExtractor from @DhiruKholia https://github.com/kholia/exetractor-clone/blob/unstable/ArchiveExtractor.py. It’s usage is simple too:

$ python ArchiveExtractor.py servant.exe

In a matter of seconds, ArchiveExtractor will extract all files into the ‘output’ folder. Easy, right?

Want to take a sneak peak at the source code? In the end it’s not everyday that we have the opportunity to see some original malware code!! You can find a copy of both the binary and the source for this sample on my GitHub account. Go through the code, analyze it, play with it (play safe!) and leave us your comments on this interesting piece of malware:

- What does it do?

- What is the attacker’s goal?

- How does it communicate with the command and control infrastructure?

- Does it use any obfuscation or encryption?

- How does it achieve persistence?

- How is having access to this code useful to you, as a defender?

I’ll be analyzing some aspects of this sample in detail in coming diaries as we look at the opportunities we have as defenders to detect and react to the artifacts created both on the endpoint and on the network. In the meantime, have fun with it. Happy analysis!

--

Ismael Valenzuela, GSE #132 (@aboutsecurity)

SANS Instructor & Incident Response/Digital Forensics Practice Manager at Intel Security (Foundstone Services)

| Application Security: Securing Web Apps, APIs, and Microservices | Orlando | Mar 29th - Apr 3rd 2026 |

Comments

Just in case you don't know: ALL executable installers and self-extractors are EVIL (and defect per design too).

Anonymous

Mar 18th 2016

9 years ago