Lessons learned from playing a willing phish

Replying to phishing e-mails can lead to some interesting experiences (besides falling for the scams they offer, that is). Since it doesn’t require a deep technical know-how or any special expertise, it is something I recommend everyone to try out at least once, as it can lead to some funny moments and show us that the phishing trade doesn’t always operate in the way we might expect it to.

When it comes to phishing e-mails, unless they are successful, highly targeted, or part of a larger attack pattern of a single threat actor, most of us tend to just delete the messages and quickly forget them. But sometimes it can be quite instructive to bait the phishers and play a potential victim of the scam they thought up. Although most of us won’t be able to come close to making the attacker join our fictitious religion and send us his photograph with his breast is painted red, along with a sum of money[1], the experience can still be quite interesting and teach us a lot.

If you chose to bait phishing attackers, it is advisable not to do so from your own e-mail account but use another one – ideally a “burner” account you don’t mind losing. This brings us to one of the first things pretty much anyone who tries to bait phishers learns – unless it’s a targeted attack, the scammers don’t (for obvious reasons) check whether the e-mail address they receive a reply from was part of the list of addresses they originally send the phishing to.

If we reply to a phishing e-mail within a couple of days after receiving it, chances are that phishers will get in touch with us. Phishing messages usually ask us (again, for obvious reasons) to reply to a different address than the one we (seemingly) received it from. For run of the mill phishing attacks, most threat actors stop (or are forced to stop) using any e-mail addresses associated with a phishing campaign fairly quickly, although this is not always the case. The campaign which prompted me to write this diary actually surprised me very much in this regard. And, since it was otherwise quite “normal”, we’ll use it as an example of how phishing campaigns may progress.

It started all the way back in August with an e-mail in which the author, claiming to be an attorney of a recently deceased wealthy man, promised me untold riches if I act as a relative of the deceased in order to get his vast fortune as an inheritance. It contained the following text in both English and Spanish.

From: Ike Kekeli <ikekekeli77@gmail.com>

To: undisclosed-recipients:;

Subject: Hi ,

Date: 13 Aug 2019 17:29 (GMT +02:00)

Hi,

Firstly, let me identify myself without any intention of equivocation

on this business opportunity to you my name is Ike Kekeli , A

Fiduciary bank Attorney At Law ?s wish to know if we can work

together. I would like you to stand as the surviving beneficiary to my

deceased client ( Mr . Gilbert ) who made some deposit of $7.9 Million

Dollars to be transferred to any possible safe account with your good

assistance.

He died without leaving any WILL and any registered next of kin and as

such the funds now have an open beneficiary mandate. Kindly get in

touch with me through my email address ( barristerikek <at> gmail.com ) for

more guidelines to the repatriation of this fund.

Regards,

Attorney Ike Kekeli . ( Esq )

I only noticed the e-mail when I was going through my phishing quarantine nearly two weeks after it was delivered and although the e-mail wasn’t special in any way (this sort of lure is quite common in phishing), and I wasn’t holding much hope with regards to the address still being active, I decided to reply. The reaction from the attackers didn’t take long – within 10 minutes, I had another e-mail in my inbox, this time asking me for my personal information. Although this sort of reaction time puts even many professional support teams to shame, it is actually not uncommon for phishers to reply to their potential victims very quickly. Sometimes, it might take a day or two to get a reply back, but in many other cases (especially in cases of BECs), five or ten minutes may be more than enough time.

After exchanging couple of messages with “attorney Ike”, he sent me couple of forms pre-filled with the personal information I’ve provided earlier and asked me to send these to a “bank” – a different e-mail address used by the attackers. This is another quite common technique used by malicious actors as it lends the scam much more credibility if multiple “trustworthy” parties seem to be involved. The reply from the bank contained a spectacularly looking letter in a PDF from the “bank president” asking me for a copy of my ID card.

Sending the phishers a document can be a good way to determine their external IP address – I send the “bank” a TinyUrl link which redirected a visitor to my logger script, which, after saving the IP address of the visitor and some additional information, redirected them to what seemed to be a corrupted JPEG file. Since most phishers don’t have a high level of technical expertise or security awareness, they tend to click pretty much anything one sends them, so it didn’t take long to get a hit on the logger script and determine where the attackers were from.

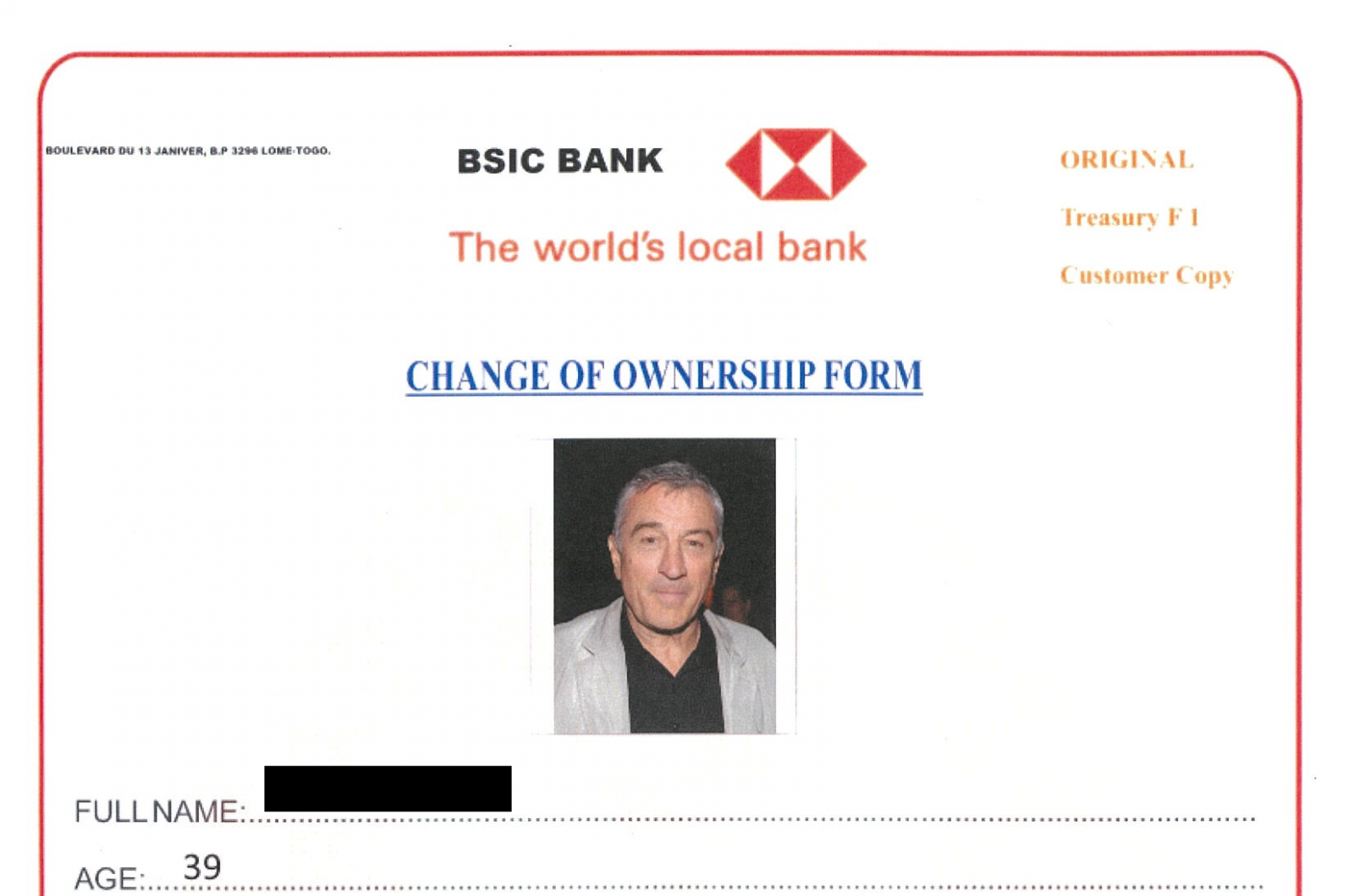

The “bank” afterwards asked me to send in a filled in form with my personal information and a photo. I’m the first to admit that I can be a bit juvenile in such cases – I usually pick one of the more famous actors out there, as you may see bellow, and see whether I get any interesting reaction from the phishers. Although it is surprising, they usually don’t notice it.

It was at this point that both “Ike” and the “bank” started to ask for money – since the “bank” sent me an account number to transfer the money to (account in a different bank, then the one they were acting as, of course), I contacted the real bank with the account information and after exchanging couple of additional messages broke off the contact with the scammers. Getting the account number and providing it to the bank which hosts the account is usually the most one can do in such cases, without straying outside the reasonable ethical boundaries. It took about two weeks for the phishers to give up after I stopped responding at the beginning of September.

The most interesting part of this phishing campaign came only last week, when I received a new message from “Ike”, promising me a reward for helping him although the deal didn’t work out. That is not so unusual, what is – at least in my experience – quite unique is that the message was sent from the same e-mail address the attackers used during our original interaction.

And this is, so far, the last lesson which interacting with phishers has taught me – although I would have expected that any e-mail address used for phishing could not stay active for so long, there are some (or certainly at least one) which have been used for more than a quarter of a year and are still being actively used.

[1] https://419eater.com/html/joe_eboh.htm

-----------

Comments

I work as a security analyst and I am keen on understanding the following from your write up:

"I send the “bank” a TinyUrl link which redirected a visitor to my logger script, which, after saving the IP address of the visitor and some additional information, redirected them to what seemed to be a corrupted JPEG file."

are you able to share information about the script and JPEG file, this would be very useful in attributing where a phishing email may come from in such cases

Thanks

Anonymous

Nov 27th 2019

6 years ago

Anonymous

Nov 27th 2019

6 years ago

The "corrupted JPEG" was just a file full of random bytes with a JPEG extension.

Anonymous

Nov 28th 2019

6 years ago