Cyberbunker 2.0: Analysis of the Remnants of a Bullet Proof Hosting Provider

This post was written by SANS.edu graduate student Karim Lalji in cooperation with Johannes Ullrich.

“Cyberbunker” refers to a criminal group that operated a “bulletproof” hosting facility out of an actual military bunker. “Bullet Proof” hosting usually refers to hosting locations in countries with little or corrupt law enforcement, making shutting down criminal activity difficult. Cyberbunker, which is also known as “ZYZtm” and “Calibour”, was a bit different in that it actually operated out of a bulletproof bunker. In September of last year, German police raided this actual Cybebunker and arrested several suspects. At the time, Brian Krebs had a great writeup of the history of Cyberbunker [1].

Figure 1: “Seized” banner placed on the Cyberbunker website

According to the press release by State Central Cybercrime Office of the Attorney General over 2 petabytes of data were seized including servers, mobile phones, hard drives, laptops, external storage and documents. One of the sites, C3B3ROB, seized by the state criminal police listed over 6000 darknet sites linked to fraudulent bitcoin lotteries, darknet marketplaces for narcotics (with millions of Euros in net transactions for Marijuana, Hashish, MDMA, Ecstasy), weapons, counterfeit money, stolen credit cards, murder orders, and child sexual abuse images [2].

Several individuals involved with Cyberbunker are currently undergoing a criminal trial in Germany. To pay for legal expenses, the principles behind Cyberbunker sold the Cyberbunker IP address space to the Dutch company Legaco. Legaco agreed to route the Cyberbunker IP address space to one of our honeypots for two weeks, to allow us to collect some data about any remaining criminal activity trying to reach resources hosted by Cyberbunker.

The IP address space included 185.103.72.0/22, 185.35.136.0/22, and 91.209.12.0/24, which comes down to about 2300 IP addresses. We collected full packets going to the IP address space and set up listeners (mostly web servers) on various ports.

Traffic Summary

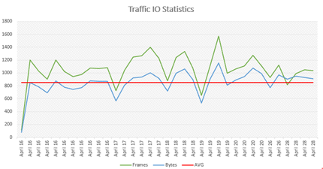

Figure 2: Traffic volume to Cyberbunker IP addresses.

Across all IP addresses, we received about 2 MBit/sec of traffic. The traffic did not target all IP addresses at the same rate. Instead, IP addresses used for popular web sites received more traffic.

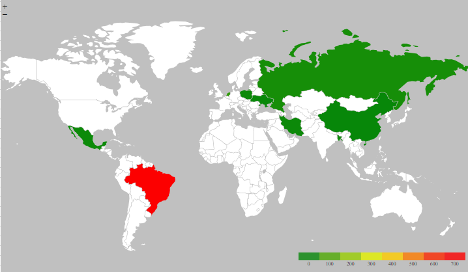

Figure 3: Countries of origin Cyberbunker traffic.

The "heat map" above shows the geographic distribution of incoming bytes where the source IPs reside in the CyberBunker networks. Moderate amounts of traffic are generated from Iran, various European countries as well as Mexico. Interestingly, the highest amount of traffic was generated from Brazil.

IRC Bot Traffic

Port 80 traffic was directed to a web server. We noted immediately that some of the traffic was not HTTP traffic, but instead IRC traffic. Bots sometimes use port 80, hoping it will evade firewall rules and inspection.

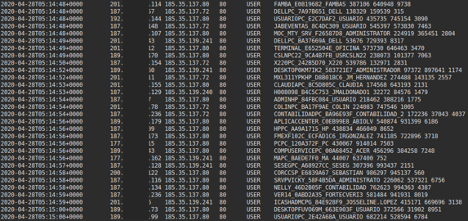

The following image shows several IP addresses accessing a subset of destinations within the CyberBunker scope as logged by Apache. The payload shows an IRC "USER" command along with what appears to be a series of computer names.

Figure 4: IRC Traffic Sample

Close to 2000 unique computer names and over 7000 unique source IPs that follow a similar request pattern are present in the traffic sample collected. When a single "computer name" was isolated with timestamps, the intervals between requests were exactly 1min and 30sec - indicating automation and potential C2.

Phishing

We also identified various phishing sites that are still receiving traffic. These phishing sites attempt to impersonate RBC (Royal Bank of Canada), Apple, Paypal, and others.

The domain apple-serviceauthentication.com.juetagsdeas.org continued to receive hits during the analysis period. Running a DIG command against this domain resulted in an NXDOMAIN response; however URLScan.io indicated that the IP address hosting this site belongs to the malicious network in question under the name "ZYZtm." At the time of the analysis, 54 other domains appear to be in the phishing category are associated with the single IP address of 185.35.138.158. One of the hosts on this IP address is psrepair.3utilities.com which, according to URLScan.io screenshot feature, shows a credential harvesting page for Chase Bank.

Figure 5: Phishing Page (via urlscan.io)

Ad Network

The webserver we configured to receive the traffic destined to the Cyberbunker IPs received traffic looking for banner ads placed with the "getmyads.com" ad network. Like many legitimate businesses, criminals advertise their services on other websites via banner ads and referral links. The site being advertised is often communicated as part of the URL to retrieve the appropriate banner, or to credit the correct advertiser. Strings included in the ad requests suggest that the network was used to advertise adult services, and in some cases, these sites may have been associated with the sexual abuse of children. Distributing material depicting the sexual abuse of children was one of the charges levied against the proprietors of Cyberbunker.

At the time we collected our data, most of the requests for these URLs originated from the "Majestic" search engine.

According to archive.org, getmyads.com was most active from 2016 to 2018, with some updates made late in 2019. It appeared to provide a multi-level marketing style ad network at times, which provided generous referral fees. The last update made in 2019 shows a "Seized Back By the Government of Cyberbunker" banner, likely in response to the German government placing "seized" notices on various Cyberbunker related sites following the raid.

Figure 6: getmyads.com image retrieved from archive.org

Other Traffic

The analysis also uncovered other notable behavior such as encrypted binary HTTP communication tied to known malware signatures and presumed to be C2 communication, backscatter from what appears to be previous DDoS attacks and DNS resolution of sites that host illicit pornography (involving animals). Additional details can be found in the SANS Reading Room paper. [3]

[1] https://krebsonsecurity.com/2019/09/german-cops-raid-cyberbunker-2-0-arrest-7-in-child-porn-dark-web-market-sting/

[2] https://gstko.justiz.rlp.de/de/startseite/detail/news/News/detail/landeszentralstelle-cybercrime-der-generalstaatsanwaltschaft-koblenz-erhebt-anklage-gegen-acht-tatve/

[3] https://www.sans.org/reading-room/whitepapers/threathunting/real-time-honeypot-forensic-investigation-german-organized-crime-network-39640

Karim Lalji | LinkedIn

Johannes Ullrich | LinkedIn | Twitter

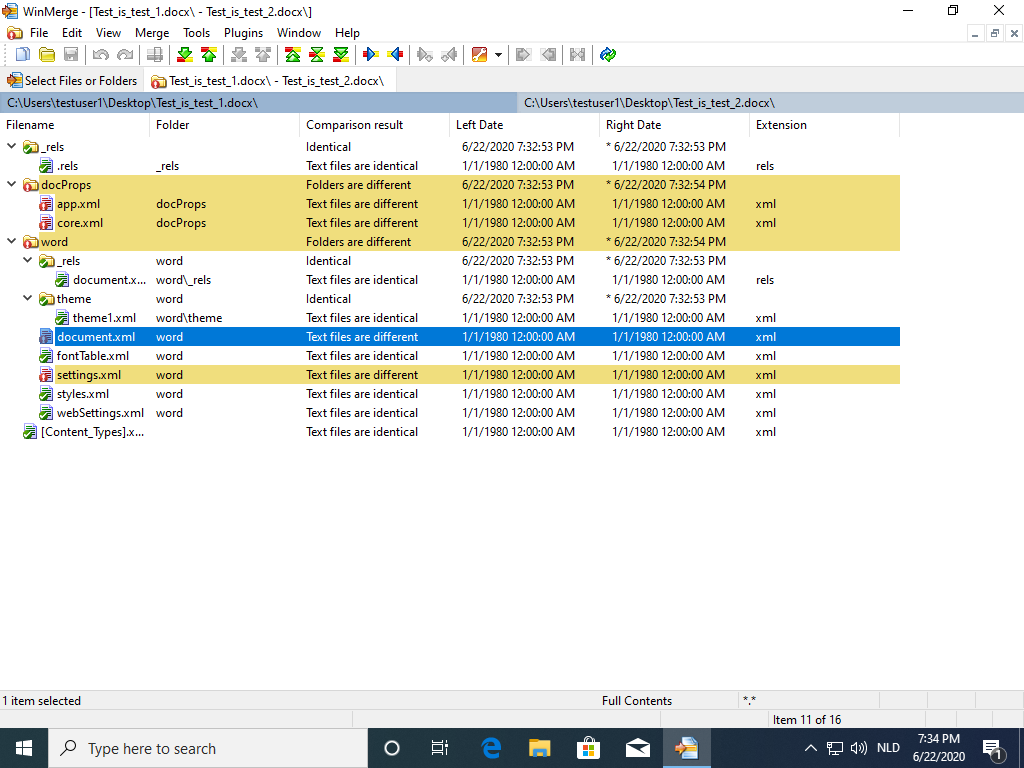

Comparing Office Documents with WinMerge

Sometimes I have to compare the internals of Office documents (OOXML files, e.g. ZIP container with XML files, …). Since they are ZIP containers, I have to compare the files within. I used to do this with with zipdump.py tool, but recently, I started to use WinMerge because of its graphical user interface.

WinMerge is a free Windows tool to compare files.

It is capable of comparing files stored inside archives: this is exactly what Office documents like .docx, .xlsm, … are.

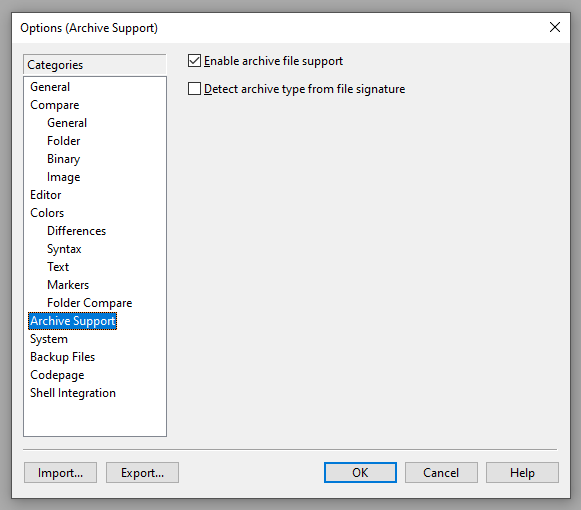

First I have to change a setting so that WinMerge will recognize archive files like ZIP files based on their content too, and not only their extension.

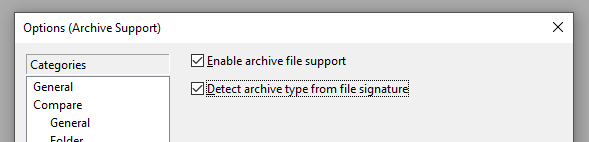

Then I open the 2 Word documents. The first .docx file is a Word document with the text "This is test 1", the second Word document is an edited copy with the text "This is test 2".

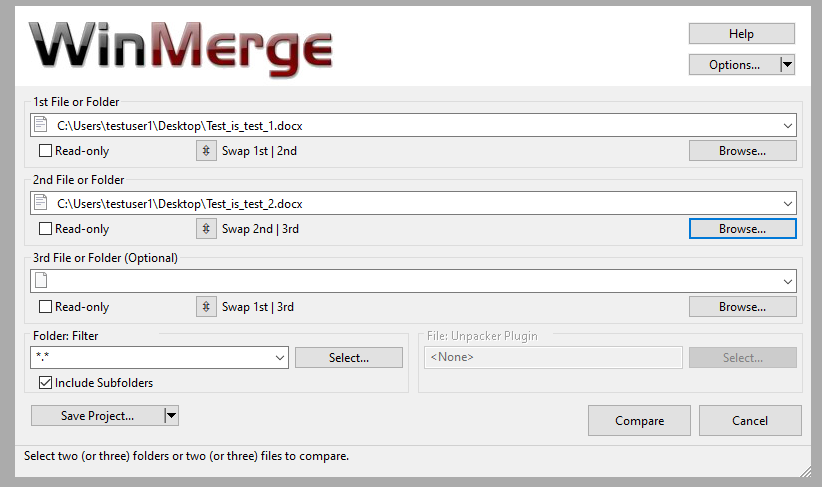

I make sure that all comparisons are visible, and expand all subfolders:

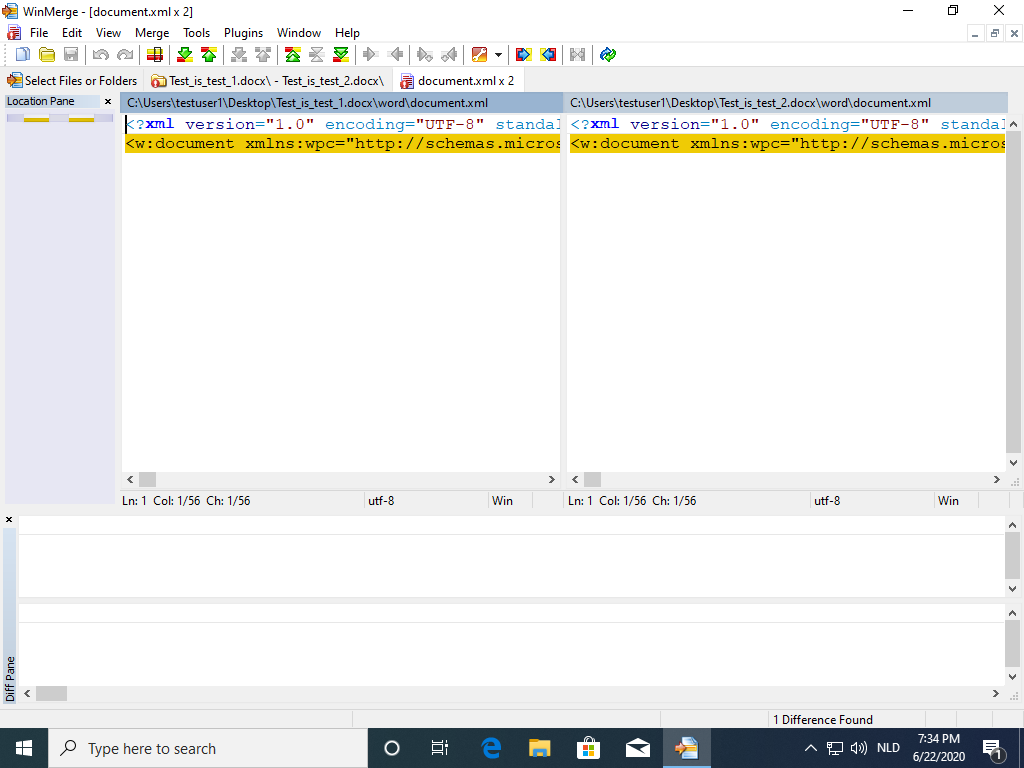

It is not a surprise that document.xml is one of the files that is different: it contains the words I typed into the document and then altered:

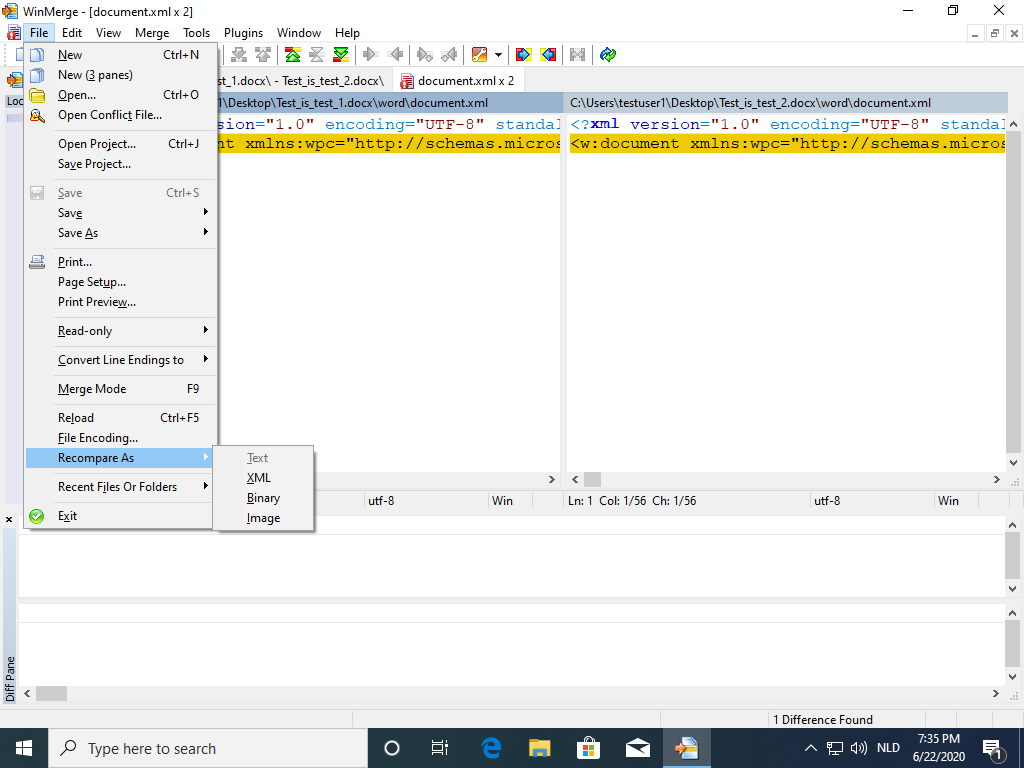

WinMerge can also be used to compare XML files:

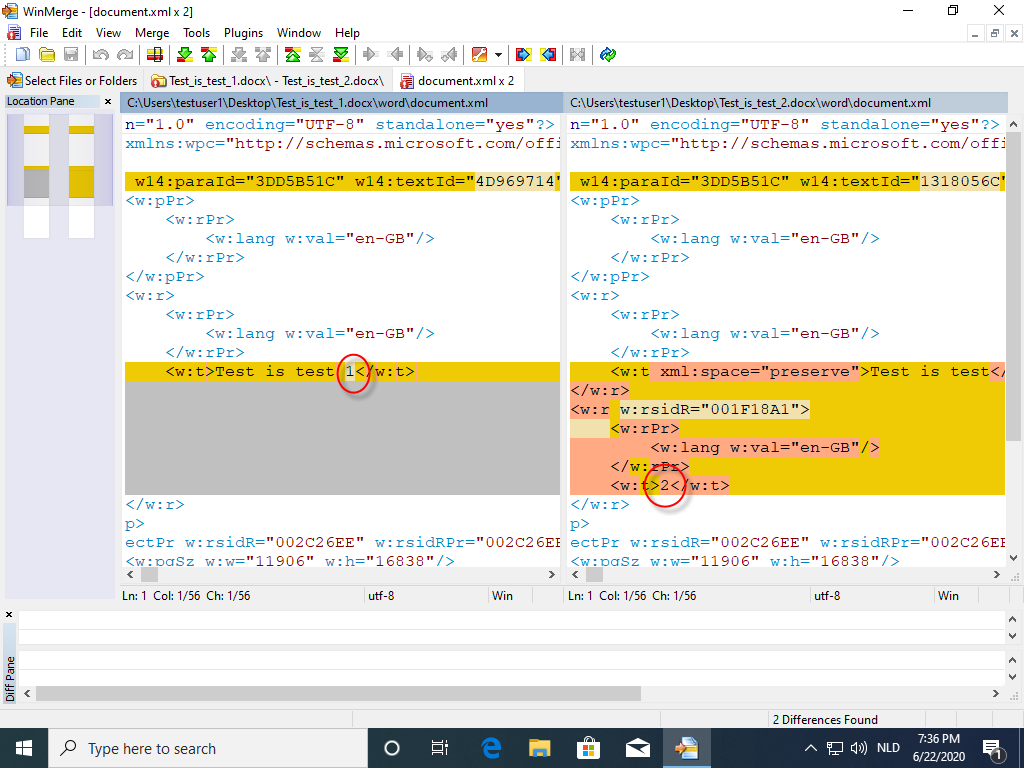

And then it is easier to see the changes I made:

Didier Stevens

Senior handler

Microsoft MVP

blog.DidierStevens.com DidierStevensLabs.com

Comments